Creating Strong Community-Academic Partnerships

Each Neighborhood Health Partnerships Program report provides a helpful snapshot of community health data. However, the reports are just one of the many building blocks that come together in a true and mutually beneficial community-academic partnership. In this action tool, we provide a guide to considerations and resources for building strong partnerships.

Many of the most effective projects that have improved community health were built on strong partnerships. Community-academic partnerships, in particular, can be an asset to both neighborhood organizations as well as researchers.

All parties can benefit from community-academic partnerships:

- The community benefits because a strong partnership is more likely to meet community needs.

- Community partners can also gain access to academic tools that can help them do their work more efficiently. Good evaluation data can help community partners make their work more sustainable.

- Researchers benefit by tapping in to community partners’ existing networks. Additionally, as covered in Community Tool Box’s section on Community-based Participatory Research, researchers benefit by receiving more complete and accurate information from the community.

Valuing everyone at the table

Strong community-academic partnerships usually aren’t built quickly or without tension. Partners often have different priorities. To avoid unnecessary friction, partners must understand and value the perspectives of all parties at the table.

It can be helpful to think of your seat at the table and what you can do understand the other people who are present. In the chart below, please select the statement that feels most true to your role in this work.

I am a Community Partner

Partnering with researchers offers many benefits for community partners. The ways in which a community partner work with a researcher can look different depending on what the researcher studies. A researcher may be able to provide data to a community partner that can be helpful when applying for funding or grants. Researchers may also be able to provide funding to community partners who partner with them on grants. Researchers can also help community partners figure out how to design or modify interventions to make the community healthier. Finally, researchers can help spread the word about the successful work going on in the community through their connections to statewide and national networks.

Even if both groups have similar goals, the ways that community partners and researchers go about their work can cause tension. Researchers are generally concerned with collecting and using data, which takes time and effort. They want to use evidence to understand how and why a community becomes more healthy. Community partners, on the other hand, are often focused on meeting the immediate needs of the people that they serve. They have years of experience through living and working in their community. They can feel that they already know what “works” and does not work – no additional evidence required.

Community partners should be leaders in the discussion around research to ensure that the community’s needs are being met and that community members are empowered and valued throughout the process. One resource for community partners is the Building Trust Between Minorities and Researchers website provided by the University of Maryland Center for Health Equity. This site has several helpful resources for community partners such as: the Importance of Research and Research, Community and You.

For Wisconsin-based community organizations interested in working with a researcher, the following resources may provide a good place to start:

- Wisconsin Public Health Research Network

- University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research

- Clinical and Translational Science Institute of Southeastern Wisconsin

- Marshfield Clinic Research Institute

- UW-Madison Experts Database - Browse or search by topic (e.g. “diabetes”)

- UW-Milwaukee Research page - Browse research centers and partnerships

I am a Researcher

Community partners are generally concerned with making a direct impact on their community and are often focused on service provision. They want to make local residents healthier and their neighborhoods stronger. For community partners to value research and evaluation, it must be relevant and useful for their community.

Even if both groups have similar goals, the different ways that community partners and researchers go about doing the work can cause tension. Researchers are generally concerned with collecting and using data, which can take time and effort. They want to use evidence to understand how and why a community becomes more healthy. Community partners, on the other hand, are often focused on meeting the immediate needs of the people that they serve. They have years of experience through living and working in their community. They can feel that they already know what “works” and does not work – no additional evidence required.

It is important to recognize that some community organizations may have had a history of bad experiences with researchers in which they ended up feeling more used than supported. Many communities, particularly communities of color, may not trust outside researchers. This can be especially true for health researchers due to research abuses of the past, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, as well as ongoing experiences of discrimination in health care settings. To build relationships with community partners, it is helpful to understand community development work. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps has a detailed Action Learning Guide on partnering with residents. It is important to include community partners as leaders throughout the research process to ensure that the community’s needs are being met and that community members are empowered and valued. Allocating grant funding to community partners is also important.

To help bridge gaps between minorities and researchers, the University of Maryland Center for Health Equity's website Building Trust Between Minorities and Researchers was created to help both researchers and communities understand what is needed to build equitable community-academic partnerships.

For researchers working in areas associated with clinic and health systems, the following articles offer some examples of what a community-academic partnership can look like:

- Community-Based Participatory Research: Its Role in Future Cancer Research and Public Health Practice

- Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity

- AHRQ Activities Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Care Disparities

For researchers working in public health, the following articles offer examples of what a partnership can look like in that context:

I am a NHP Navigator

For the Neighborhood Health Partnerships (NHP) program, Navigators are the people or organizations who often work with both community partners and researchers. Navigators can help to build trust and relationships between community partners and researchers. They are often the people who help to explain the needs and wants of the different groups in the partnership. They may be skilled at explaining data in a way that is relevant to communities, or skilled at presenting neighborhood priorities in a way that makes sense to researchers.

For the NHP program pilot, Navigators are also the people who are trained to share reports. They should work with both researchers and community partners to put the reports, and the WCHQ data contained within, into the proper context. Navigators should not necessarily be making the decisions on what researchers and community partners should work on, however they can help ensure that researchers and community partners have what they need to take action. They can also help to connect community partners and researchers when there are opportunities for collaboration.

If you are interested in becoming a navigator contact: nhp@hip.wisc.edu.

Building partnerships

Strong community-academic partnerships can take many forms and work in many different ways but there are some core practices that support ethical and responsible local data use:

- Focus on shared priorities (what are researchers and community partners commonly interested in working on)

- Meet partners’ primary interests

- Enhance organizational capacities (all parties should be able to do more because of this partnership)

- Develop/build on long-term partnerships (these partnerships are often built over years, not months)

- Take time to build trust

- Facilitate reciprocal learning (everyone grows in their knowledge)

- Adapt interventions/strategies to cultural and local contexts (meets the needs of the unique community and the people who live there)

- Value local knowledge

- Engage or train investigators from communities impacted by research

- Resource communities as partners (make sure local people have what they need to fully participate as partners)

- Facilitate action on research in service of the communities impacted

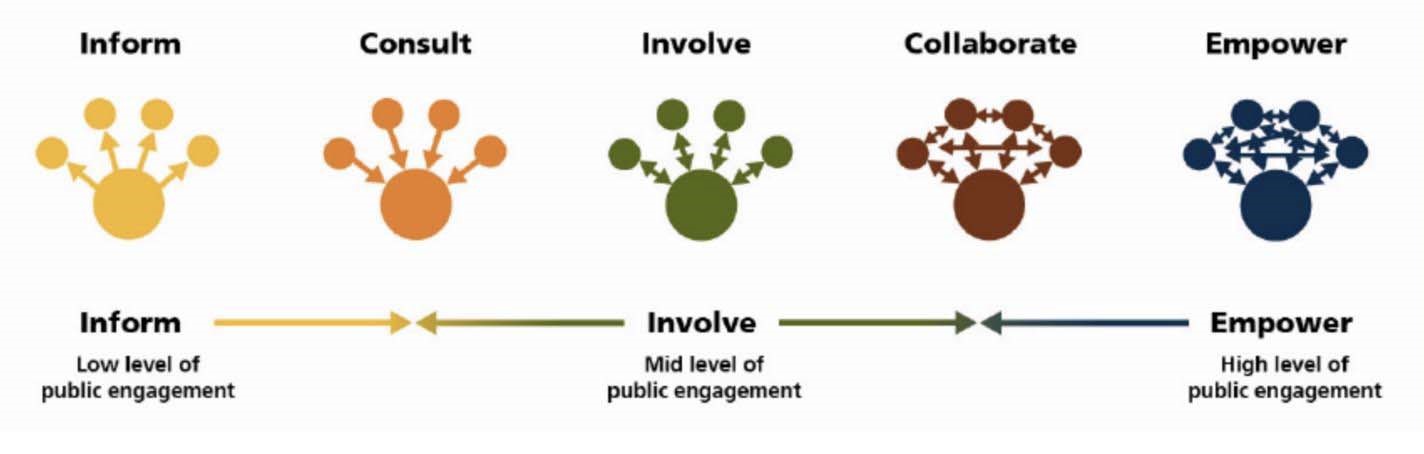

In some instances, community-academic partnerships can be rather shallow. For example, the academic partner only informs the community, information flows in one direction from the researcher to the community. Or community members give consulting feedback on plans already created by the academic partner. While this type of communicationcan help establish connections, these shallow partnerships may not achieve broader improvement in health outcomes.

To build the strongest possible community-academic partnerships, communities and researchers should build to a place of shared leadership. In a shared leadership model, strong bidirectional trust is built between researchers and communities and final decision making is at the community level. The National Institutes of Health has a detailed report covering the Principles of Community Engagement (pdf) which can help partnerships move towards shared leadership.

Community-Academic Partnerships and the Reports

The local health data contained in the reports can be a useful tool for community-academic partnerships. The ZIP code level health data contained in the reports allows community practitioners and academic researchers to more precisely pinpoint neighborhoods experiencing health disparities and inequities.

Backed up by local health data, community-academic partnerships can make it possible to try fresh, innovative interventions built with community wisdom and scientifically supported methods. Community-academic partnerships can help people understand why a particular intervention was successful in a community and whether that success can be repeated in other communities.

Coming Soon! Examples from the Field

Once the NHP pilot is complete, the NHP team will add examples of ways that people from across Wisconsin have used the reports as part of the work to build and strength community-academic partnerships.